By Dr. Sheryl L. Walker

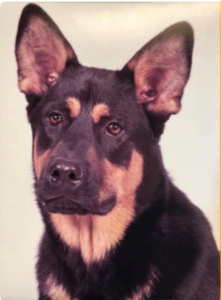

Young German shepherd/

Rottweiler mix Gerhardt reported with approximately six bite events at the initial behavior consult © Gerhardt’s Guardians

Of all my years studying animal behavior and consulting with individual clients and animal shelters, there was one case in particular that stood out, partly because it featured two incredibly dedicated guardians. Ironically, it was also one of my most complex cases.

It was a case of canine anxiety- and pain-induced dog-directed aggression involving a young neutered male named Gerhardt who had approximately six bite events between August 2009 and November 2012, beginning when he was approximately 7 months old.

The environmental trigger, initially, seemed to be mealtimes, during which Gerhardt’s guardians Lynn and Lee* fed Gerhardt out of a metal bowl. However, upon further investigation, another environmental trigger was identified as Gerhardt being in close proximity to other dogs.

History

Lynn and Lee adopted Gerhardt from a shelter at the age of 8 weeks. He and his litter of four siblings were fostered from the age of 4 weeks, when they were found in an abandoned home in January 2009. Research shows that that removing puppies from their moms too young can be detrimental to their behavioral development (Battaglia, 2009; Pierantoni et al., 2011; Plujimakers et al., 2006; Slabbert and Rasa, 1993). This has also been shown in other species, such as mice and rats (Ito et al., 2006; Kikusui et al., 2004).

Lynn and Lee took Gerhardt to puppy training classes starting when he was 12 weeks old. They also took him to weekly puppy playgroups and socialized him with people, other dogs, and new environments. Ideally, these experiences can set the foundation of a behaviorally sound dog (De Meester et al., 2005; Foyer et al., 2013; Howell et al., 2015).

Gerhardt had a history of either one or more symptoms of allergies when he was younger, including severe itching/licking, vomiting, and/or diarrhea. When he was 6 or 7 months old, he had large patches of hair loss on both lateral sides due to constant licking. This lasted for a month, then the hair reappeared with no treatment and grew back normally.

His guardians attributed these behaviors to a sensitive stomach and worked through several different brands of dry dog food to eliminate the problem. However, such symptoms can also be indicative of anxiety (Camps et al., 2019; Dreschel, 2010).

The first bite event happened in August 2009, when Lynn and Lee took Gerhardt to visit a family member. During mealtime, Gerhardt was eating from a metal bowl in the kitchen and the family member’s dog (an Australian kelpie named Rosie) snuck up behind him with the intention of stealing the food. Gerhardt whipped around and air snapped with no contact (Level 1) (Yin, 2012).

Lynn and Lee moved residences in June 2010. Lynn relocated first and, due to work constraints, Lee moved 11 months later. During those 11 months, Gerhardt lived with Lynn but spent occasional weekend retreats with Lee. The original residence was moderately sized (1,275 sq. ft., three bedrooms, two full bathrooms), and was well-suited for two humans and a puppy. There was no fenced-in yard, so Lee walked him at least three times a day around the neighborhood.

They had downsized during their move, into a 1,000- sq. ft. townhouse with two bedrooms/bathrooms. There was a fenced-in yard that enclosed both units of the duplex. The attached neighbor had a young, unneutered male boxer who was very people- and dog-friendly. When Lynn lived by herself, she would take Gerhardt to the local off-leash dog park a few times a week for social time with other dogs and physical exercise.

The second bite event happened in September 2010, during one of the previously mentioned weekend retreats. Lee worked at a local school and took Gerhardt to work with him for a few hours. A coworker entered Lee’s office unannounced, along with her 1-year-old neutered mastiff Brutus, who she had brought to work that day. Gerhardt, who had been calmly chewing on his rawhide, attacked Brutus with a bite wound near his eye (Level 3) (Yin 2012).

Excitable

When Lee moved to be with Lynn, they started to notice a difference in Gerhardt’s behavior. He was super excitable when they both came home. They would take him outside right after they arrived, ignore him for several minutes till he was calm enough to greet. If they let him outside and closed the door to take their shoes and coats off, he would jump and paw at the sliding glass door with a high-pitched bark.

The third bite event happened in March 2012. It occurred at their house when they were dog sitting for a friend. The guest dog was a 3½-year-old intact male beagle named Buddy. Lee fed both dogs in the same room and Gerhardt attacked Buddy when he got too close to the food bowl (Level 2).

The fourth bite event happened in September 2012, again at Lynn and Lee’s house when dog sitting for another friend. One of the dogs was a 5-year-old neutered male beagle/basset hound mix named Yoshi. The other dog was a 6-month-old intact female Labrador retriever/Italian greyhound mix named Salem, who was very nonconfrontational.

Initially, Gerhardt’s guardians had him in the kitchen with a baby gate separating him from the living room. Their friend then brought Yoshi and Salem into the house and the dogs greeted each other through the baby gate for about 10 minutes. Lynn and Lee then opened the baby gate and the dogs got along fine.

A little later, Lynn was walking through a small hallway with Gerhardt and Yoshi on either side of her. At this time, Gerhardt attacked Yoshi, which resulted in two puncture wounds: one on his ear and one on his muzzle (Level 3) (Yin, 2012). Lynn pulled Gerhardt off Yoshi and took him outside and closed the door.

While she was tending to Yoshi’s wounds, Gerhardt was barking a high-pitched bark while obsessively pawing on the sliding glass door.

The fifth bite event happened in November 2012. Lynn and Lee had brought him to daycare/boarding overnight. A staff member said that after an hour of outside time, Gerhardt was waiting by the door to go inside. When the door opened, apparently another dog was standing there and Gerhardt attacked him, inflicting a bite wound (Level 3) (Yin, 2012). The staff used a horn and squirt bottle to interrupt the attack, and kept Gerhardt in his kennel for the rest of his stay, away from other dogs.

The sixth bite event happened three weeks later. Lynn and Lee’s family were visiting with their two dogs: Rosie the Australian kelpie mentioned in the first bite incident (who was now 10 years old), and a 2-year-old neutered male hound mix named Jack.

Lynn and Lee had Gerhardt in the kitchen behind a baby gate when everyone arrived. He barked with his hackles up, but quickly became calm and wiggly when greeting the family members. After 10 minutes, the family members brought Rosie and Jack into the fenced-in back yard to explore.

After another 10 minutes, Lynn and Lee brought Gerhardt outside, on leash, to the outside of the fence, so there was a barrier between him and the guest dogs. The dogs sniffed each other and Gerhardt play bowed, so they decided to let him into the fenced-in area. His interactions with the two other dogs were relatively calm at that time.

Gerhardt and Jack exchanged growls once, but Lynn and Lee redirected Gerhardt, which diffused the situation. After dinner, their family members brought in their luggage and asked the dogs to move, at which point Gerhardt attacked Rosie, inflicting a wound on her right leg (Level 3) (Yin, 2012).

Initial Consultation

It was after this latest incident that Lynn and Lee contacted me. At the time of consultation, Gerhardt was 3½ years old and weighed 93 pounds. He was cautious with strangers inside and outside the home, and Lynn and Lee reported having a wonderful relationship with him, in spite of the stress that he caused them. He was in excellent physical health, and displayed overt body language signals during the consultation, including panting, pacing, huffing, and whining that were indicative of conflict and anxiety (Luescher & Reisner, 2008; Tiira et al., 2016; Salonen et al., 2020).

The consultation included an in-depth behavior history form which served as the foundation of discussion. By coincidence, the neighbor’s dog, a young, intact boxer named Joe was in the yard and at the sliding glass door while Lynn was feeding Gerhardt treats. His body stiffened, his hackles raised, and he growled at Joe. Lynn walked in between the two dogs to try to distract Gerhardt and he air snapped toward her, making no contact (Level 1) (Yin, 2012), a classic example of redirected aggression (Wilde, 2015).

Dog guardians often report that their dogs have bitten “without any warning” (Reisner, 2014). Indeed, while some dogs show very clear signs that they are uncomfortable with a situation, others give much more subtle behavioral cues indicating their discomfort, and sometimes guardians are unable to recognize those subtle changes. Although Gerhardt was quick to escalate in this instance, his body language was very clear (e.g., hackles up, tail up, head tall) (Chin, 2020).

He also had a “Highly Sensitive” personality type (Braem et al., 2017; Dube et al., 2020). When his anxiety was high and other dogs didn’t immediately listen to his communication, he would escalate to the next behavior to communicate that he needed space: air snapping or biting. With his also being sensitive to trigger stacking (Henley, 2019), Gerhardt’s anxiety was impairing his ability to function in a human world.

Behavior Modification Plan

A. Environmental Management and Enrichment

The frequency of the bite incidences and history of wounds justified my recommendation that Gerhardt see a veterinary behaviorist for possible anxiolytic intervention. An environmental management plan was suggested to begin immediately, so future problems could be avoided prior to the consultation with the veterinary behaviorist.

Lynn and Lee were instructed to no longer feed Gerhardt in the kitchen or from a bowl, and instead use food puzzles or his regular food as treats while training. They were also instructed to have absolutely no dog visitors or interactions with other dogs until they had seen the veterinary behaviorist. To provide environmental enrichment, it was suggested that they take Gerhardt on walks at least twice a day for at least 20 minutes each time, during low neighborhood traffic times.

B. Observing and Decoding Dog Body Language

Dog communication is much more complicated than many people think (e.g., tail wagging doesn’t necessarily mean a happy dog). Gerhardt’s guardians were advised to purchase Barbara Handelman’s book Canine Behavior so that visual depictions of dog body language could help them better interpret precursors to anxious behaviors.

C. Relax on Bed

Because high arousal states are a catalyst for anxiety-based aggression, Lynn and Lee were taught how to train Gerhardt to relax on a dog bed. This helped keep his arousal state at a comfortable level as the parasympathetic nervous system tells the body that it’s “okay” to relax.

A basic introduction to clicker training helped teach Lynn and Lee how to capture and reinforce calming behaviors, such as when Gerhardt laid down on his dog bed, deep sighed, or placed his head down on the bed.

D. Counterconditioning

Counterconditioning works well as a tool to change a dog’s emotional responses to environmental stimuli. Predictability decreases conflict anxiety (i.e., people are interesting, yet scary; the dog park is so much fun, yet too overwhelming) because the animal has more control over his environment.

However, caution must be taken in order to ensure the dog doesn’t form an association with environmental stimuli that always occur prior to the anxiety-eliciting stimuli. For example, Gerhardt’s guardians only put him behind a baby gate whenever visitors would be entering the home, so he formed a pretty solid association of the baby gate being a predictor of something negative happening.

The Look at That game was developed by Leslie McDevitt for reactive dogs. The concept of the game is that dog guardians would click for the behavior of looking at something scary/frightening/arousal-provoking while being under “threshold” of reactivity, and immediately give their dog a high-value treat.

Gerhardt’s guardians were instructed that while on walks, if Gerhardt heard or saw another dog, they would click then treat. If Gerhardt’s body language seemed relaxed, they would continue on their walk. But if his body language seemed tense, they would then turn around and walk back home. The goal was to start changing the emotions associated with other dogs from anxiety-provoking to calm and relaxed (i.e., conditioned emotional responses).

Follow-Up

Lynn and Lee brought Gerhardt to see a veterinary behaviorist in January 2013 and a copy of the environmental/behavioral management plans were provided at that time. As Gerhardt’s anxiety and high arousal levels were antecedents for the attacks, emphasis was placed on decreasing anxiety and environmental triggers. The veterinary behaviorist prescribed Reconcile (e.g., Fluoxetine), which is a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) (Ibanez & Anzola, 2009).

As psychoactive drugs can take several weeks to take full effect, the next consultation was scheduled six weeks after the Reconcile was started. Lynn and Lee reported seeing improvements in Gerhardt’s anxiety levels, as well as improvements in his engagement with them, i.e. without hyperexcitability. Additionally, they were taught the basic fundamentals of how to introduce Gerhardt to a basket muzzle.

During a six-month follow-up consultation, Gerhardt’s guardians mentioned that it seemed as if the Fluoxetine had stopped working. Meanwhile, Gerhardt now had a diagnosis of mild to moderate hip dysplasia, spinal disc disease, and arthritis, confirmed with X-rays. The anxiety-induced aggression may have had a pain component all along. Lynn and Lee took Gerhardt to see the veterinary behaviorist again, and he was prescribed Deramaxx to help with the pain. The anxiolytic was changed from Fluoxetine to Gabapentin.

The next consultation was three weeks after Deramaxx and Gabapentin had been started. Lynn and Lee reported being elated with great improvements in Gerhardt’s anxiety levels, as well as “having their dog back.” His personality was yet again goofy and playful, he was able to settle on his dog bed whenever the cue “bed” was said. In addition, Lynn and Lee seemed more at ease during the consultation.

Discussion

Gerhardt’s guardians were extremely dedicated to their dog, and were open, willing, and flexible to incorporate environmental and behavioral changes that were in their control in order to help decrease his stress levels. They were also receptive to the idea of anti-anxiety medications, which made the recommendation to see a veterinary behaviorist easy to bring up in discussion with them.

Chronic anxiety in dogs is multifaceted and can manifest in several different ways. Chronic pain that wasn’t treated disguised itself as anxiety. The anxiety manifested as hyperarousal, air snapping, and bites that caused puncture wounds to other dogs. The focus was initially on environmental management to eliminate all the known triggers (e.g., not having any dog guests to the house; not being around other dogs in general), and consultation with a veterinary behaviorist.

This case was extremely emotionally charged for all stakeholders involved: Gerhardt, Lynn and Lee, their visitors, their guest dogs, and the professionals who collaborated on the case. Chronic anxiety can absolutely disrupt the human-animal bond, and this dog was very lucky to have his humans so invested in his behavioral welfare. Kudos to the entire team.

*Some names have been changed to protect the privacy of the individuals involved.

See original article for full Reference List.

This article was first published in BARKS from the Guild, May 2021, pp.34-39. Read the full article From Reactive to Relaxed.

For more great content on all things animal behavior and training, you can sign up for a lifetime, free of charge, subscription to the digital edition of BARKS from the Guild. If you are already a subscriber, you can view the issue here.

About the Author

Sheryl L. Walker Ph.D holds a master’s degree in behavior analysis and a Ph.D. in animal behavior and sheltering. She also operates WAGS: Wonderful Animal Guidance Services in Lafayette, Indiana, specializing in puppies. She has recently been awarded her Certified Applied Animal Behaviorist (CAAB) certification, and her current research interests are puppy socialization and training.