written by Niki Tudge

Much of what we do in everyday life is all about choices. At any given moment we can work or we can do something more pleasurable, let’s say take our dogs for a walk. I can choose to do some work or train my dogs. I could then go to the beach or go to the store. I could food shop or go for a massage. I could deposit money in my bank account or buy a lottery ticket. I could train my dogs or schedule a session with a client.

There are a number of variables that exert control over my responding in these choice situations such as the reinforcement rate, the quality of the reinforcer, the reinforcement magnitude, and whether there is a delay with the reinforcement. For example if working at my computer (a powerful reinforcer for me) can be done now but scheduling an appointment with a client is not urgent then I will choice to work at my computer. If my client appointment has a deadline and I am due to get paid by them for 8 x one-hour lessons then I am more likely to schedule the appointment now as the reinforcement has greater magnitude or is qualitatively a more potent reinforcer even though it is delayed.

Choice situations arise when concurrent schedules of reinforcement are available in our environment. Training my dogs, visiting the spa, going to the beach, working at my computer, these all operate on their own schedule of reinforcement. But there is a choice between the response alternatives.

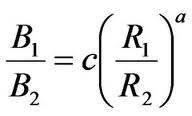

One phenomenon which was identified in laboratory studies using nonhumans is the “matching law.” The matching law theorizes that given two concurrently available response alternatives the relative rate of responding equals the relative rate of reinforcement. In other words if there are two response options and response option 1 provides two times the rate of reinforcement provided by option 2 then there will be two times the rate of responding on option 1 as appose to option 2.

One phenomenon which was identified in laboratory studies using nonhumans is the “matching law.” The matching law theorizes that given two concurrently available response alternatives the relative rate of responding equals the relative rate of reinforcement. In other words if there are two response options and response option 1 provides two times the rate of reinforcement provided by option 2 then there will be two times the rate of responding on option 1 as appose to option 2.

A good human example is consider the possibility that you need to speak to a friend, and there are two telephone numbers available for this friend, home or cell. If in your experience you are twice as likely to get through to your friend on the cell number as you are on the home number then you are likely to call the cell number twice as often as you would the home number. This is matching law.

So how does this affect how we train our dogs? We have all heard of errorless learning, I like to think of it as guided learning. I believe we should offer our dogs, during acquisition of a new behavior, as much help and assistance as possible. The more often they get it right the more reinforcement they receive the more likely they are to choose that response in the future.

Let’s look at the “sit” behavior. In a training session we can “lure” or we can “capture” I always ask the question of our student trainers. How many “sits” can you lure and reinforce in 60 seconds? How many “sits” can you capture and reinforce in 60 seconds. More importantly when you are not offering guided learning in between your capture trials don’t be fooled into thinking your dog is not getting reinforced for sniffing, standing, moving, breathing, looking at you. Your dog is getting reinforcement from somewhere, elsewhere, everywhere. Yes a concurrent schedule!

What is your experience with this, would love to hear from you

Herrnstein, R.J. (1970). On the law of effect. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 13, 243–66.