By Angelica Steinker and Eileen Anderson with additional contributions by Jan Casey and Niki Tudge. Originally published in BARKS from the Guild, October 2014.

In this series of photos Papillon Bella, is

showing an array of overt and subtle facial

expressions that convey her emotions. Clockwise from top left: fear, confidence, joy, anger.

Photos of Bella by Preval Photography

The fundamental goal of any behavior modification program should be to improve the dog’s (1) and owner’s emotional states, both during and after the process. If emotional, genetic or medical information is omitted from the functional assessment process however, the ensuing behavior modification plan will be incomplete, which not only runs the risk of recommended interventions being inappropriate and misdirected, but may also have disastrous consequences. Unfortunately, behavior myopia such as this is an all too common occurrence in our industry.

From a dog’s point of view, the most damaging aspect here is the complete disregard for his emotional state. It can be particularly catastrophic when covert or subtle behaviors are ignored as, arguably, they are the most important information a behavior consultant has. But we are all prone to focusing on what is most obvious. For example, if a dog is engaging in overt behaviors such as barking and lunging, it can overshadow nuance and make us miss the more subtle behaviors. When this occurs, we actually overlook our obligation to improve the animal’s quality of life – even though we might be presenting a potentially effective behavior modification program.

Dog trainers have an ethical obligation to do everything they can to improve the quality of life for both the dog and the owner. Having completed a behavior modification program, dogs should feel safer and happier. Similarly, the process should create dogs who are more resilient because of the improved baseline regarding joy and happiness – which also leads to a more desirable result for the owner.

Causes of Behavior Myopia:

Focus on Operant Conditioning

This dog is raising her paw which, in this case, is an overt appeasement gesture. Paired with her anxious facial expression this indicates she feels unsure or uncomfortable. The raised paw is often misinterpreted as the dog “wanting to shake hands,” which is another example of behavior myopia in action

Dog training tends to live in a world of operant conditioning. In the light of this bias and a failure to include respondent conditioning in a training protocol, emotional states (as indicated by subtle behaviors) are often ignored. There is usually much talk about incompatible behaviors and the various reinforcement schedules, but an operant approach only modifies the overt behavior, if that. This method falls short from the ideal we should all be striving for: leaving both dog and owner with an improved emotional state.

Lack of Consideration of Emotions and Their Subtle Indicators

If a dog is barking and lunging at a stimulus then he is usually fearful or angry. If the behavior modification protocol does not address his emotional state then it is flawed. A customized ethogram is a useful tool here to ensure all bases are covered.

Disregard or Ignorance of Dog Body Language

In order to interpret subtle behaviors, dog trainers need to understand canine body language. Some dogs are just hard to read, no matter how experienced the trainer. Certain breeds are stoic and simply “quiet” in their non-verbal communication. Sometimes a dog’s behavior can be globally suppressed from the use of punishment and/or negative reinforcement and these dogs can be particularly dangerous and difficult to work with.

Ignorance of or Confusion about Thresholds

There is often a lack of clear understanding amongst the dog training community regarding physiological and behavioral thresholds.

The most pertinent thresholds are:

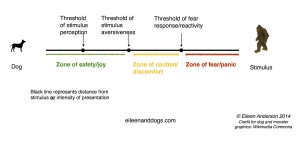

• Perception: this is the place or level at which the animal becomes aware of a stimulus through its sensory organs.

• Reactivity: this is the point at which the dog’s sympathetic nervous system engages and manifests as the barking/lunging/growling threshold that people often focus their training on. Here, the dog experiences what is usually a fear or anger response, which includes a cascade of biochemical reactions and respondent behaviors such as pupil dilation, evacuation and shutdown of the gastro-intestinal system, and changes in respiration – all of which are antithetical to a solid counter conditioning program.

Bella is feeling mild stress about being picked up (above). Her tongue flick and glazed eyes are subtle behaviors

• Stimulus Aversiveness: this threshold lies between the first two and is the point at which exposure to the stimulus is aversive but the animal is not necessarily having a full-blown fear response.

Often, trainers are only aware of obvious, reactive behaviors and unaware of the small changes that occur as a stimulus becomes gradually more aversive to the animal. Performed effectively and ethically, counter conditioning and desensitization (CC/DS) should be over the threshold of the animal’s perception but under the threshold of stimulus aversiveness. This is what we call ‘The Safe Zone’.

Lack of Education Regarding Mental Illness and Undiagnosed Physical Illness

Lack of education and experience regarding mental illness, neurological problems and the stigma of mental illness are huge issues in the dog training industry. Some trainers are not trained or sufficiently skilled to identify a dog who may be neurologically (i.e. has a head injury or brain damage) or mentally ill (i.e. has a psychiatric condition). Many do not involve veterinarians or veterinary behaviorists in cases involving aggression, anxiety or phobias because of a lack of awareness they may require medication as well as behavior modification.

Mental illness can be hard to identify. While it is not the role of the dog trainer or behaviorist to diagnose, we do need to sound the alarm bell if there is a physical problem – and this includes psychiatric conditions. A dog who has a urinary tract infection will not house train. Likewise, a dog with a mental illness such as Obsessive Compulsive Disorder will not be able to learn to stop jumping on people if that is his compulsion. The training will not be successful because the biochemistry has already decided the outcome.

Vets are trained mostly to look for physical causes for behavior rather than psychiatric ones. It can be helpful to provide a note for the vet which states something like, “Can you please evaluate for possible anxiety disorder?” Or, “Is this dog ataxic, could it be he has a head injury?”

Canine Separation Distress is another challenging disorder that can be easy to miss. The condition often requires both behavior modification and medication. For example, in one case, after a long period of misdiagnosis, a dog was diagnosed by three different veterinary behaviorists as having “virtual separation distress.” Whenever his owner turned his back, the dog would grab what the owner had last touched and begin to chew it destructively. The owner never actually left the dog alone without crating him. As such, the dog did not exhibit the behaviors normally associated with separation distress, so it had been missed. Setting up a video camera and leaving the dog alone (not in a crate) immediately showed behaviors consistent with separation distress. The crate had been managing the behavior problem but not resolving it. With medication and behavior modification the dog was able to improve greatly.

Thunderstorm Phobia is a disorder that may require the use of medication in tandem with behavior modification, but often the sensitization to storms continues regardless. In cases like this behavior myopia has been known to result in the monstrously inhumane and unethical use of aversive stimulation. This involves shocking the thunderstorm phobic dog for destructive behavior when, in fact, he is having a panic attack that is not being medically controlled.

There are probably many undiagnosed and undiagnosable illnesses that afflict dogs and can lead to behavior myopia within the modification process. It should be noted that, just because we do not have a clear understanding of an illness, it does not necessarily make it impossible to detect. For example, Milky the dog was prone to poor impulse control and aggression. Initially he responded to medication and the aggressive behavior completely subsided. However, after a few years the problem returned. The owner took Milky to a neurologist for an MRI and, while the neurologist stated Milky was abnormal on the exam, the MRI was clear. The neurologist pointed out that the absence of evidence is not evidence of absence, as it was her opinion that this dog was definitely suffering from some sort of neurological disease.

The Functional Assessment

The Subtle Face of Disgust: Bella strongly dislikes orange rind. When given one to sniff she responds with a disgusted facial expression. This a subtle behavior to most observers as she does not bark, lunge or bite, but simply displays the facial expression and a slight head turn followed by a short stare with an annoyed expression at the human who presented the rind. Humans and canines share many facial expressions. Charles Darwin was the first person to propose the universality of facial expressions and Paul Ekman found this to be accurate in humans in the 1970s. Today we know that dogs and other mammals share our emotional brain structures and brain chemistry (Jaak Panksepp Affective Neuroscience: The Foundations of Human and Animal Emotions Series in Affective Science, Oxford University Press, 2004).

The process of the functional assessment systematically identifies the relationship between behavior and the environment so that efficient and effective solutions can be developed (Niki Tudge BARKS from the Guild: June 2012, page 35).

The functional assessment includes:

1) The Informant Interview, where anecdotal information about the problem behavior is obtained from owners

2) The Direct Observation Phase, where the problem behavior is observed and the relationship between the differing variables, antecedents, behavior and consequences are measured and correlated

3) The Functional Analysis Phase, which tests the trainer’s hypothesis. The intended final product is a contingency statement the professional has confidence in

In many cases however, only the first two steps are conducted, leaving out the important contingency statement in Step 3, which details the antecedents, behaviors and consequences in measurable terms and describes the relationship between them (Niki Tudge BARKS from the Guild: June 2012, page 35).

What follows is a case study that illustrates unreservedly the importance of a complete, accurate and insightful functional assessment.

Owner Stephanie sought help because her dog Boomer was redirecting aggression onto Jessie, the other dog in the household. During the initial intake process Stephanie maintained fights only occurred when she was present; Boomer “demanded physical attention” for about 10 minutes of every hour Stephanie spent with the dogs. During one of these interactions Boomer and Jessie began fighting. The trainer concluded this was because Stephanie was “spoiling” Boomer with attention. As a result, she was advised to withdraw any affection from Boomer, which the trainer said would decrease or stop Boomer “resource guarding” her and, therefore, the fights. In reality though the fights continued and actually got worse.

The initial behavior assessment based on the trainer’s interview with the owner and observation of the dog can be seen here:

Antecedents

Presence of Stephanie

Physical touch of Boomer

Presence of both Boomer and Jessie

Behavior

Dog fight

Consequences

Distance increase between the fighting dogs

Catharsis of tension

Since the initial advice to stop giving Boomer attention resulted in the fighting getting worse, the trainer re-evaluated the case and interviewed Stephanie a second time. More importantly, the trainer observed Boomer more carefully to look for subtle behaviors and then completed a customized ethogram.

The following subtle behaviors were noted:

• Boomer would tongue flick and hold his breath if Stephanie moved away and/or toward Jessie.

• Boomer’s facial expression when “demanding” attention was very anxious. His brows were pulled up and together and his commissure, corner of the mouth, was wrinkled. This had been previously missed.

• When Boomer was being petted by Stephanie this expression relaxed. His muscles relaxed slightly and his respiration slowed and his anxious facial expression melted away.

Completing an accurate functional assessment in this case helped the trainer theorize that Boomer had an anxiety disorder and, as such, had become dependent on his owner for physical touch and comfort. This important piece of the puzzle had been missed previously. This is a perfect example of behavior myopia in action.

Anxiety was consequently added to the list of antecedents as the prime factor. This allowed the creation of a new behavior modification plan which included:

1) seeking a veterinary behavior consult

2) adding a relaxation protocol

3) adding a counter conditioning/desensitization program based on reducing anxiety

Boomer’s dependence on his owner to relieve his anxiety was gradually reduced through direct treatment of the anxiety. In addition, the veterinary behaviorist addressed Boomer’s underlying anxiety disorder.

In Boomer’s case, the behavior myopia occurred during the initial interview when the trainer inaccurately assessed Stephanie as the cause of the problem. Significantly, the trainer did not acknowledge the subtle behaviors and failed to recognize that the dog’s frequent demands for touch were, in fact, an indicator of anxiety. Instead, the overt “attention seeking” behavior was labeled as demanding. The trainer’s focus was also drawn to the number of fights and their intensity.

It is obvious here how the behavior modification process can lead to two different outcomes. Fortunately in this case the trainer realized her mistake but mistakes like this can be life altering in the most tragic way, with both dogs and humans potentially at risk.

In behavior modification, often our goal is to reduce, replace or modify a given behavior. When we hear that a dog who used to be comfortable with other dogs is now reactive after a bad fight at the dog park, our goal is usually to return the dog to baseline and help him become the way he was BEFORE the bad dog fight. On the surface this sounds reasonable but it is actually behavior myopic. Behavior modification has an obligation to improve the baseline and to change a state of fear to a state of joy.

The consequences of behavior myopia can range from minimal to far-reaching. A common result is that behavior consultants “climb the ladder” of a so-called humane hierarchy and end up using aversive interventions because the original intervention “did not work.” Shocking or using otherwise aversive stimulation is unethical with any animal but is even more heart-breaking with an animal who is mentally or physically ill.

Many times an inaccurate functional assessment leads to accidental flooding. For example, a dog who is undergoing behavior modification may be “under threshold” at a distance of say 100 ft. Ideal counter conditioning works very closely to the perception threshold and avoids moving toward the aversiveness threshold. A dog will only be able to experience joy if he is in the safe zone. Relief should not be confused as joy.

To avoid flooding, it is essential that behavior consultants create a behavior modification process where the dog is only exposed to a stimulus that is NOT threatening. Exposures should be potentially joy eliciting. This means ALL exposures must be graded in a way that they do not trigger fear, anger or any kind of failure. This would include flooding or causing the dog to show mild, moderate or severe signs of stress.

Compiling an ethogram – which MUST include subtle behaviors – will help identify the dog’s threshold. Assessing the threshold using only overt behaviors is likely to make CC/DS fail. A dog is only in his safe zone when he is happy and/or playful and/or relaxed. Any other zone comprises variations of aversive exposure or flooding and will not yield ideal results. Nothing is more damaging than the accidental or deliberate use of flooding.

It’s Okay to Be Wrong!

As trainers, there are a number of options we can keep in our toolboxes to make sure we avoid falling into the behavior myopia trap:

Cognizant Behavior Consulting

Cognizant Behavior Consulting (CBC) advocates for the improvement of the emotional lives of dog and owner, for critical thinking through self-awareness, and avoiding labels when possible. Blanket statements that a dog is “dominant” or “needy” are unhelpful; describing what behavior looks like is almost always more useful.

In practice, CBC draws from multiple branches of science to make an accurate functional assessment (including the physical, mental and emotional state of the dog) and then creates and implements a successful behavior modification program accordingly.

Critical thinking

Critical thinking helps separate truth from fiction. Sometimes owners may make up stories to explain why their dog is engaging in a specific behavior but these may not match the facts. By pushing ourselves to be fact-based we can provide better behavior modification.

Emotional Contagion

All of us have experienced joining in with someone laughing when we have no idea what the joke actually was. In the same way, a dog can pick up on the emotions of a tense owner. This process is known as emotional contagion.

Beings vary in their abilities to send and receive emotions. While some are strong ‘senders’ because their subtle behaviors are fairly obvious, others are weak senders. In dogs, these are the stoic ones who are much more difficult to read. Likewise, beings can be strong receivers (able to read emotions in others easily) or weak receivers (finding it challenging to read others’ emotions).

A Cognizant Behavior Consultant will implement emotional contagion in the dog’s favor. Many trainers recommend a technique called “the jolly routine” to be used during counter conditioning. This means the owner and trainer display happy emotions and “throw a party” for the dog during a training approximation, a potentially stressful situation, or if a training mistake has occurred. They may also pair a “jolly routine” with a certain stimulus to “infect” a dog with happiness and prevent a failure or an undesirable association between a stimulus and stress.

Avoiding Projection and Denial

Projecting occurs if a trainer accidentally or deliberately blames his own shortcomings on the client or dog. The problem with projections is that they are not based on facts. When assessing a dog, the Cognizant Behavior Consultant should be aware of his own issues, biases and common projections so they do not interfere with the training and coaching process.

Denial is closely related. This too can lead to inaccurate functional assessments. None of us can entirely prevent projection and denial, they are an integral part of human behavior. Being aware of these issues and owning them, however, disarms the damage they may otherwise cause to a more ideal outcome.

Behavior consultants need to be honest with themselves about their individual shortcomings. For example, some trainers might be aware they do their best coaching with clients who are compliant and love their dogs. Clients who are burned out or who have never had a reinforcement history with their dogs may be a big challenge for some of us, but this should not mean we do not work with them. Instead, we must work very hard at being non-judgmental and supportive.

No Quick Fix

Ultimately, it is important that behavior consultants and trainers strive to master both the art and science of the functional assessment. We should all make use of CBC, not just to include behavior analysis, but also all the necessary components of the behavior modification process that will improve the service we deliver. Make a commitment to avoid behavior myopia in all its forms by pushing yourself to your creative limits and maximizing your self-awareness. There are no quick fixes to behavior problems, but positive, joy-centered CBC is a fun process that is self-reinforcing. While behavior myopia can be seductive, the alternative solution is an infinitely more powerful and joyful experience.

(1) For the purposes of this article we will reference dogs most frequently but the concept applies to all animal training and behavior modification programs, as well as human-to-human interactions.