© Can Stock Photo / focalpoint

Introduction

To some degree we are all products of cultural conditioning that instills within us biases and prejudices that can impregnate our behavior towards others. The term and concept microaggressions was first identified and termed in the 1970’s by Chester M. Pierce. The term refers to “subtle, stunning, often automatic, and non-verbal exchanges which are ‘put downs’” (Pierce, Carew, Pierce Gonzalez, & Willis, 1978, p. 66). Racial microaggressions have also been described as “subtle insults (verbal, nonverbal, and/or visual) directed toward people of color, often automatically or unconsciously” (Solorzano et al., 2000).

In a paper titled Microaggressions in everyday life: implications for clinical practice, the authors noted that the term “racial microaggressions” best described the phenomenon in everyday life. Simply stated by Sue et al (2007) “microaggressions are brief, everyday exchanges that send denigrating messages to people of color because they belong to a racial minority group.”

In 2020 The Pet Professional Guild initiated its Inclusivity Division. The key goal of this division is to support initiatives for the organization to be more purposeful in enhancing inclusivity and diversity both within its membership and its wider community. The Guild website states, “We stand with all those working for widespread social change to eradicate racism and injustice. We join the outcry for greater inclusion and equity. We are committed to having tangible and actionable goals behind that urgency.” (Pet Professional Guild, 2022).

Belonging to an organization that welcomes, empowers and embraces diversity and inclusivity is not only socially responsible but positively impactful for all the stakeholders. It is now well referenced across a review of the literature that the impact diversity and inclusivity have on an organization is very powerful to the organization’s well-being. There are “effects on collective accuracy and objectivity, analytical thinking, and innovativeness” (Gompers and Silpa, 2008).

Uncivil Behavior

In August 2021 I wrote a short blog about uncivil behavior in the workplace. The blog was titled “Are you Guilty of Uncivil and Destructive Workplace Behavior?” The blog was an extract of a full article written for BARKS from The Guild titled “The Lost Art of Disagreeing without Being Disagreeable: An Urgent Need for a Return to Civility!”

Workplace civility can be defined as “behaviors that help to preserve the norms for mutual respect in the workplace; civility reflects concern for others” (Andersson, 1999).

When we fail to smile at a colleague or contemptuously smirk at another person’s suggestion, gather in small clans or cliques or ostracize others through exclusionary practices, these seemingly innocuous behaviors can be very costly to the morale of others and efforts to build an inclusive community. As a reader you may be thinking, as you rush ahead to these examples, that you cannot be or are not an uncivil person. You do not behave in a way that is bullying or harassing or intimidating to others. Or do you? The same question can be asked of whether you express microaggressions during interactions with others.

Below are examples of behaviors that are deemed uncivil.

- A failure to notice or acknowledge another person’s presence such as ignoring them in a group situation, or their arrival to a group setting.

- If we ignore a person’s greetings or well wishes as they approach or leave our company.

- Bullying or behavior that comes in the form of leveraging the power of cliques to ostracize particular individuals.

- The use of hostile, intimidating or crude language towards or about something or somebody.

- To either gossip or spread gossip about another irrespective of its factual accuracy.

- Surreptitiously assigning blame to a third party for a workplace mistake based on unclear expectations, particularly if this mistake or person is then a topic of gossip.

- Sabotaging an individual’s performance through lack of communication or support.

- Ignoring or downplaying an individual’s contribution in the workplace or on a project.

- Being insensitive to others’ needs with regard to personal time off, support or tolerance.

- Poor communication etiquette such as ignoring calls or email, omitting some team members from a reply, but not others. Remember civility is beyond just good manners.

- Any visual or verbal bullying behavior in the workplace is not only uncivil but can also be illegal.

- Behavior that discriminates against an individual because of an intrinsic characteristic or physical appearance is not only uncivil and immoral it can also be illegal.

As individuals we must be emotionally aware of our behavior and the impact it has on others. In the short term uncivil behavior will impede our ability to work with others and be a productive team member. In the long term it will damage relationships and other opportunities that may avail themselves.

What Do Microaggressions Look Like?

Given that we know and are now aware of what uncivil behaviors look like, what do we consider microaggressions? Recognizing and working to prevent microaggressions in our own behavior is a good first step for each of us to help promote a truly inclusive organization where all members feel truly valued. So, if microaggressions are everyday exchanges then from an objective or tangible criteria what does this actually look like from a behavioral perspective?

In 2008 Cortina “extended the notion of incivility by examining it through lenses of gender and race.” The central argument is that incivility, in some cases, is not “general” at all, but instead represents contemporary manifestations of gender and racial bias in the workplace. In other words where incivility maybe a generic behavior of some individuals, microaggressions are more selective and target specific people or individual groups. A study conducted by Cortina, Kabat-Farr, Leskinen and Huerta (2013) tested a theory that selective incivility is nothing more than “modern manifestation of sexism and racism in the workplace. “Their study found that women and people of color reported more instances of workplace incivility on the job than men and whites. There is a possibility that firms that possess a negative diversity climate may experience more occurrences of workplace incivilities in the form of “selective incivilities.” (Prieto et al 2016, P, 42).

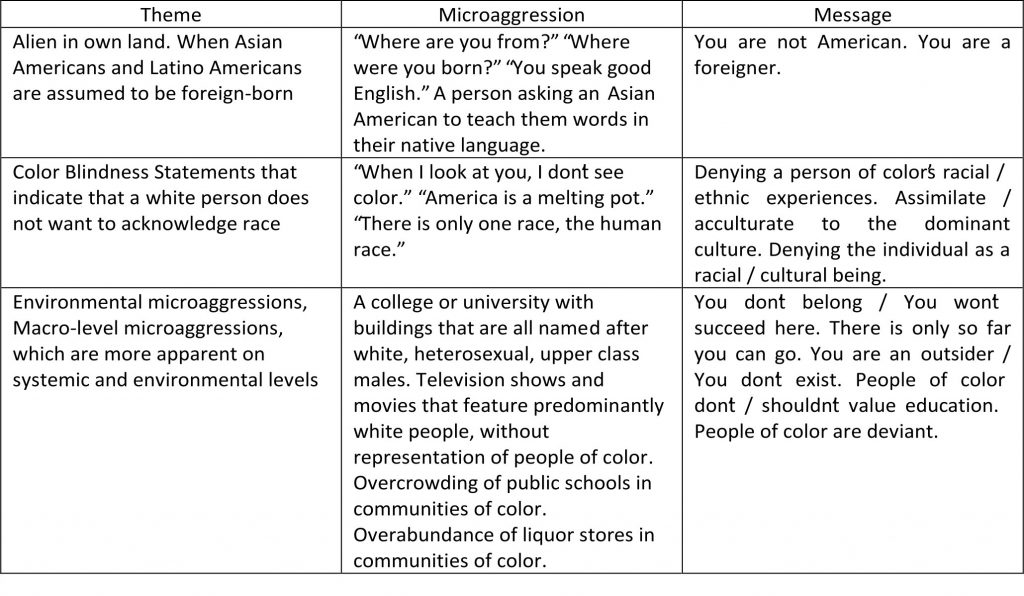

The University of Minnesota put out a document titled Racial Microaggressions. In this document they detail the “Theme,” the “Microaggression” and the “Message”. I have included some examples below:

The Momentous Institute discusses and provides examples of Gender Microaggressions. They explain “Gender microaggressions are small, seemingly innocuous comments that can pile up over time and affect a person’s sense of self and identity. These microaggressions can become so commonplace that we don’t even notice them”:

- “Boys will be boys” This dismisses a boys’ behavior based on stereotypes and almost removes any level of personal responsibility for the behavior.

- “Act like a lady” This holds girls to standards and expectations based on historical roles and not in relation to an individual girl’s personality.

- “Man up” This phrase is often used to stop men and/or boys from showing any emotions, it places unrealistic expectations on individuals just because they are male.

- “I need a few strong men to help me lift this” This can be dismissive of the physical abilities of girls or women.

- Differentiated Language. This is when comments about girls and boys are different. Think about when a girl is labeled bossy rather than showing leadership or when a boy is called the class clown rather than being a show-off!

- “You look like a princess.” This expression places all the importance on looks over any other physical, emotional or other personal characteristics or abilities.

- Using a student’s legal name rather than the name the student uses to refer to him/herself. This is dismissive of an individual’s gender or their identity.

Ethics of Care

So how do we combat not only uncivil behavior but also microaggressions?

In 1993 Tronto discussed the practice of Ethics of Care and explained that this is a practice rather than a set of rules. Organizations need to actually and really care about their stakeholders and individual stakeholders need to actually care about their colleagues and those around them. The required elements needed to drive Ethics of Care are attentiveness, responsibility, competence and responsiveness. Each individual needs to show and have a concern for others’ needs and the acceptance of those needs.

We All Need to Commit to Progress

Each of us must adopt a standpoint and readiness to consider other positions, thoughts and expressed feelings. To reduce microaggressions, the practice of an ethic of care is needed to ensure that attention is paid to the needs of diverse members, valuable stakeholders whose well-being should be viewed as essential by all other stakeholders. (Freeman 1984).

So, let’s care for each other, the organization and the individuals. Let’s all work together to implement a practice of “Ethics of Care”. Let’s all work together and individually to eliminate not only uncivil behavior but microaggressions. By doing this we should facilitate the connectedness required for attentiveness, responsibility, and competent responsiveness. I would love to hear from you on what you think we can do to expedite this and to support us growing as an organization and as individuals in a positive, diverse and inclusionary way.

Bibliography

Andersson, L. (1999). Tit for tat? The spiraling effect of incivility in the workplace. Academy of Management Review, 24: 452-471.

Cortina, L. M., Kabatt-Farr, D., Leskinen, E. A., & Huerta, M. (2008). Selective incivility as modern discrimination in organizations: Evidence and impact. Journal of Management, 39(6), 1579-1605.

Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Boston, MA: Pitman Publishing.

Gompers, Paul, and Silpa Kovvali. (2018). “The Other Diversity Dividend.” Harvard Business Review 96, no. 4 (July–August 2018): 72–77.

Momentous Institute. (2022). Gender Microaggressions – We’re All Guilty Of Them

Pierce, C., Carew, J., Pierce-Gonzalez, D., & Willis, D. (1978). An experiment in racism: TV commercials. In C. Pierce (Ed.), Television and education (pp. 62– 88). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage

Prieto, L. C., Norman, M. V., Phipps, S. T. A., & Chenault, E. B. S. (2016). Tackling Micro-Aggressions in Organizations: A Broken Windows Approach. Journal of Leadership, Accountability and Ethics, 13(3)

Solorzano, D., Ceja, M., & Yosso, T. (2000, Winter). Critical race theory, racial microaggressions, and campus racial climate: The experiences of African American college students. Journal of Negro Education, 69, 60 –73.

Sue DW, Capodilupo CM, Torino GC, Bucceri JM, Holder AM, Nadal KL, Esquilin M. (2007). Racial microaggressions in everyday life: implications for clinical practice. Am Psychol. 2007 May-Jun;62(4):271-86.

The Pet Professional Guild (2022). Inclusivity Division

Tronto, J. C. (1993). Moral boundaries: A political argument for an ethic of care. New York, NY: Routledge.

Tudge. N. J (2018). The Lost Art of Disagreeing without Being Disagreeable: An Urgent Need for a Return to Civility! BARKS from The Guild

University of Minnesota. School of Public Health. Racial Microaggressions

Listen to the PPG Advocacy Panel podcast Recognizing Microaggressions So They Can Be Managed and Avoided