This article delves into the differences of opinion regarding the philosophical approach and structure toward pet training and highlights the need for trainers – and pet owners – to be cognizant of what an animal is communicating, their emotional state, and to understand how and why they are reacting or responding to a specific situation or context

While everyday unpleasantness cannot be avoided, the application of aversive stimuli in a strategic and purposeful training, management or care plan most certainly can be. There are perfectly humane and positive alternatives that are not packaged with problematic emotional consequences such as fear, anxiety and pain © Can Stock Photo / semenovp

By Susan Nilson and Niki Tudge

Significantly, there is no consensus across the pet industry with regards to the suitability and appropriateness of the different best practice models.

In 2012, the Pet Professional Guild (PPG) worked in conjunction with Dr. James O’Heare, president of the Companion Animal Sciences Institute (CASI) and director of the Association of Animal Behavior Professionals (AABP), to deliver to its members a guided delivery system for best practice within the parameters of its Guiding Principles.

LIEBI and LIMA

This best practice works through an algorithm and levels of intrusiveness model known as Least Intrusive Effective Behavior Intervention, or LIEBI.

Meanwhile, in September 2018, the International Association of Animal Behavior Consultants (IAABC), the Certification Council for Professional Dog Trainers (CCPDT) and the Association of Pet Dog Trainers (APDT) in the United States made a joint announcement regarding their newly adopted best practice model.

The organizations stated that they were “incredibly proud” to announce their agreement of a Standard of Practice: “Through our unified Code of Ethics and LIMA (Least Intrusive, Minimally Aversive) guidelines, we promote, as a norm and a fundamental tenet, positive reinforcement training, and giving a voice to our learners as well as our clients.”

It becomes clear, then, that some of the key organizations representing pet professionals have taken somewhat differing approaches to how their members should approach the modification of behaviors and implementation of training programs.

Some have provided parameters within which members should work whereas others have provided models that allow complete autonomy for their members regarding tools, equipment and philosophy.

Scientific Approach – Tactical Approach and Methodology

According to Donaldson (2017), dog training is a divided profession: “We are not like plumbers, orthodontists or termite exterminators who, if you put six in a room, will pretty much agree on how to do their jobs. Dog training camps are more like Republicans and Democrats, all agreeing that the job needs to be done but wildly differing on how to do it. The big watershed in dog training is whether or not to include pain and fear as means of motivation.”

To compound the differences of opinion regarding the philosophical approach and structure toward pet training, there are also several factions within the professional population regarding the tactical approach to training pets and much conflict on the application of how the science is utilized.

Key Learning Theory

The key methods of learning that are applied and used for changing behavior are operant and respondent conditioning. In respondent (or classical) conditioning, the presence of one stimulus begins to reliably predict the presence of a second stimulus (Tudge, 2017).

This is not a consciously learned process; it happens automatically and without thought, e.g. Pavlov’s dogs started to salivate as they began to associate the sound of a bell with the delivery of food. In respondent conditioning, we are managing and changing emotions.

In operant conditioning, meanwhile, we are managing and changing behaviors through the control and manipulation of consequences, the environment.

The Quadrants

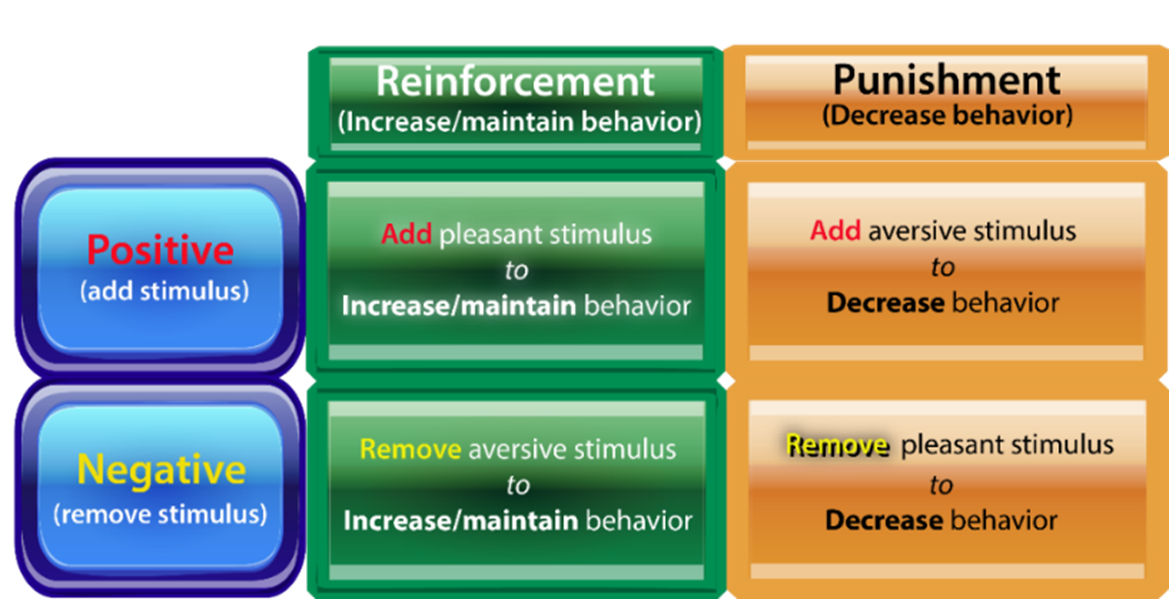

The Four Quadrants © DogNostics

Operant conditioning, defined as such because the behavior operates on the environment, takes place when a response in a given situation is reliably reinforced or punished, so there is a contingency between the response and the reinforcer/punisher.

There are four types of operant learning (known as the four quadrants): positive reinforcement, negative reinforcement, positive punishment, and negative punishment. In the descriptions detailed above, the terms positive and negative do not describe the consequence, rather, they indicate whether a stimulus has been added (positive) or subtracted (negative) to increase/strengthen or decrease/weaken the preceding behavior (Chance, 2008, p.126).

The quadrants that strengthen behaviors are referred to as reinforcements. Both positive and negative reinforcement increase the strength of a behavior due to the consequence. In positive reinforcement, a behavior is followed by the appearance of or an increase in the intensity of a stimulus.

The stimulus is something a pet seeks out, i.e. something he finds attractive or desirable, and, therefore, it reinforces the behavior that precedes it.

In negative reinforcement, a behavior is strengthened by a pet’s ability to avoid or escape an aversive stimulus, i.e. something he finds unpleasant or frightening. It is thus sometimes referred to as escape/avoid learning (Chance, 2008, p.129).

The remaining two quadrants weaken behavior and are referred to as punishments. Both positive and negative punishment decrease the strength of a behavior due to the consequence.

Punishers are aversive and something a pet works to avoid. When an aversive event is added to a situation, then positive punishment has taken place. Negative punishment subtracts something from a situation, such as privileges, and is sometimes called penalty training (Chance, 2008, p.208).

Individual Trainer Preferences

In animal training, chasms can develop due to the fact that the application of each of the four quadrants is totally dependent on the individual trainer. Each professional has their own line in the sand in terms of how they will determine, apply and justify (or not) the use of aversives, i.e. stimuli that are scary or painful for the pet.

While blanket statements such as, “We should never use positive punishment,” may be made, aversive stimuli are ever present and even the “simple use of the word ‘no’ can function as positive punishment.” (O’Heare, 2016, p.19).

How fear-provoking the word “no” is will be based purely on an individual animal’s conditioning history. If it has been paired with an electric shock, loud shout, or physical punishment, for example, then its future use will most likely elicit fear.

And while a gentle use of the same word “no” prior to removing a shoe from a pet’s mouth may also technically function as positive punishment, on a scale of pain or fear, this cannot be compared to the previous example.

States O’Heare (2016, p.19): “It is important to avoid exaggeration or excessive simplicity in the analysis. Accepting extreme arguments such as all forms of aversive stimulation are always sure to cause irreparable harm or that aversive stimulation is necessary to succeed in training leads to dogmatic positions.”

Individual Animal Responses

A critical point to understand here is that reinforcement and punishment are defined by the pet, not the trainer. For some dogs, being sprayed in the face with water may be applied as a punishment by a trainer but may be a reinforcing contingency to the dog (i.e. the dog enjoys it).

In everyday life, we are all faced with aversive stimuli from the moment we wake till the moment we go to sleep. These come in various forms, such as the alarm clock, droning or beeping signals that remind us to fasten our seat belts, arguments with colleagues or spouses, and honking horns can all serve to frustrate or irritate us and have an impact on our behavior.

It should be noted that some stimuli (for both humans and pets) are socially mediated and cannot be foreseen and/or prevented. Other stimuli, meanwhile, are contingent on our own behavior and, it may be argued, serve some greater function, such as the unpleasant taste of a poisonous plant that may prove useful as part of our survival strategy.

While everyday unpleasantness cannot be avoided, the application of aversive stimuli in a strategic and purposeful training, management or care plan most certainly can be. There are perfectly humane and positive alternatives that are not packaged with problematic emotional consequences such as fear, anxiety and pain.

We must also recognize that some aversive stimuli are merely irritating, whereas others may generate a strong emotional response and be completely unproductive.

Again, dependent on a pet’s conditioning history, what is merely an irritant for one can be devastating for another. This argues for why, as an industry and as training and behavior professionals, we need to avoid making dogmatic statements and generalizations about the behavioral sciences with no regard for the individual pet in our care.

Instead, we must avoid risking negligence by focusing purely on the animal in front of us as well as his immediate welfare needs at the hands of our training and care procedures.

This means that, rather than just speaking to the four quadrants, we must determine the impact of our intervention choices by studying the immediate emotional and behavioral welfare of each pet.

When structuring hypothetical arguments on a wholesale front about training approaches, it is also important to be careful not to apply generalizations on paper that do not play out in a training scenario.

Professionals can achieve this by possessing a comprehensive knowledge and thorough understanding of canine social behavior and communication.

The Impact of Aversive Training Methods

Ziv (2017) reviewed data from a number of studies and surveys on the relationship between the use of a variety of tools and methods in dog training.

The results show that using aversive training methods (e.g., positive punishment and negative reinforcement) can jeopardize both the physical and mental health of dogs (Tudge & Nilson, 2017).

In addition, although positive punishment is known to be effective, there is no real evidence that it is more effective than positive reinforcement-based training.

Nevertheless, despite the decades of studies we now have access to, there are still organizations, associations and councils responsible for the representation, guidance and certification of pet industry professionals that adhere to the belief that using scary and painful aversives is an acceptable – and even necessary – way to train, care for, and manage pets.

These same associations play a critical role in establishing and recommending best practices, education, leadership and technical standards in their respective arenas and with this role comes the obligation to take a transparent and consistent position on important and urgent issues, including training practices and equipment use.

This does not mean said organizations need to remove or even inhibit professional autonomy. However, a line based on research, science, and ethics should be drawn as to what are, and are not, acceptable business practices in terms of applied animal behavior (ABA), core principles, and informed consent.

And, wherever possible “practitioners should base their choices of training methods on scientific data.” (Ziv, 2017).

Do No Harm

Among professionals, it should not even need to be debated that, in the process of training, one must not physically or emotionally harm an animal. This should not even be an issue.

As such, it is our view that local authorities, animal welfare organizations, municipal animal control facilities and professional pet industry associations can no longer remain as passive observers here, but, rather, must actively shape the change in the industry by stepping forth and making the difficult and necessary decisions regarding tools, equipment and training approaches.

Consumer Transparency

While pet professional membership bodies, industry associations and credentialing bodies should be taking full responsibility for the fact that pet owners are encouraged to purchase services from their members purely by association, and through their efforts to market said members to the general pet-owning public, what this does not take into consideration, unfortunately, are the vast differences in methodology and philosophy that may exist across the membership.

In other words, there is no stated transparency in terms of the risks and benefits associated with the services provided, nor any differentiation between those members who practice a positive training philosophy and those who still risk physical and/or psychological harm to pets through their approach, philosophy and/or choice of tools.

Across these differing approaches to dog training and behavior modification, professionals may commonly be insistent on using the tools they deem to be best or most appropriate with little concern to the emotional state expressed by the pet in front of them.

Animal Emotions

All too often there is a myopia to what the pet is actually communicating, feeling, or even how he is reacting or responding. As such, subtle signs of stress, anxiety or fear may be missed due to the insistence that the chosen approach is acceptable.

For example, feeding a dog treats while undergoing a training session in a stressful environment, or with a rough hand, is not going to constitute a positive approach to the training task.

Indeed, we often see in such scenarios that the pet is too emotionally aroused to even take interest in a treat, much less actually consume one.

A possible resolution to common situations such as these may be found in the adoption of a Best Practice Model that covers the need for efficacy and efficiency in pet training while avoiding industry dogma and taking into consideration the welfare of our family pets.

References

Chance, P. (2008). Learning and Behavior. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning

Donaldson, J. (2017, January 5). Talk Softly and Carry a Carrot, Not a Stick

International Association of Animal Behavior Consultants. (2018). Announcing a new Joint Standards of Practice for professional animal behavior consultants and trainers

O’Heare, J. (2014). The least intrusive effective behavior intervention (LIEBI) algorithm and levels of intrusiveness table: a proposed best practices model. Version 6.0

O’Heare, J. (2016). Minimally Aversive Contingency Management. Journal of Animal Behavior Technology (6) 1 19-35

Pet Professional Guild. (2012). Guiding Principles

Tudge, N.J. (2017). Training Big for Small Business. (n.p.) Ingram Spark Self-Publishing

Tudge, N.J., & Nilson, S.J. (2019). The Case for Scientifically-Informed, Kind Practices. BARKS from the Guild (34) 18-26

Ziv, G. (2017). The Effects of Using Aversive Training Methods in Dogs – A Review. Journal of Veterinary Behavior: Clinical Applications and Research (19) 50-60

Resources

Best Practice [Def]. (2010). In Business Dictionary

Best Practice [Def]. (2010). Wikipedia

Friedman, S. (2010). What’s wrong with this picture? Effectiveness is not enough. APDT Journal