This article explains how a speech language pathologist uses therapy dogs in her practice to help clients improve their interpersonal and communication skills, build self-esteem and self-worth, and reduce feelings of loneliness and isolation

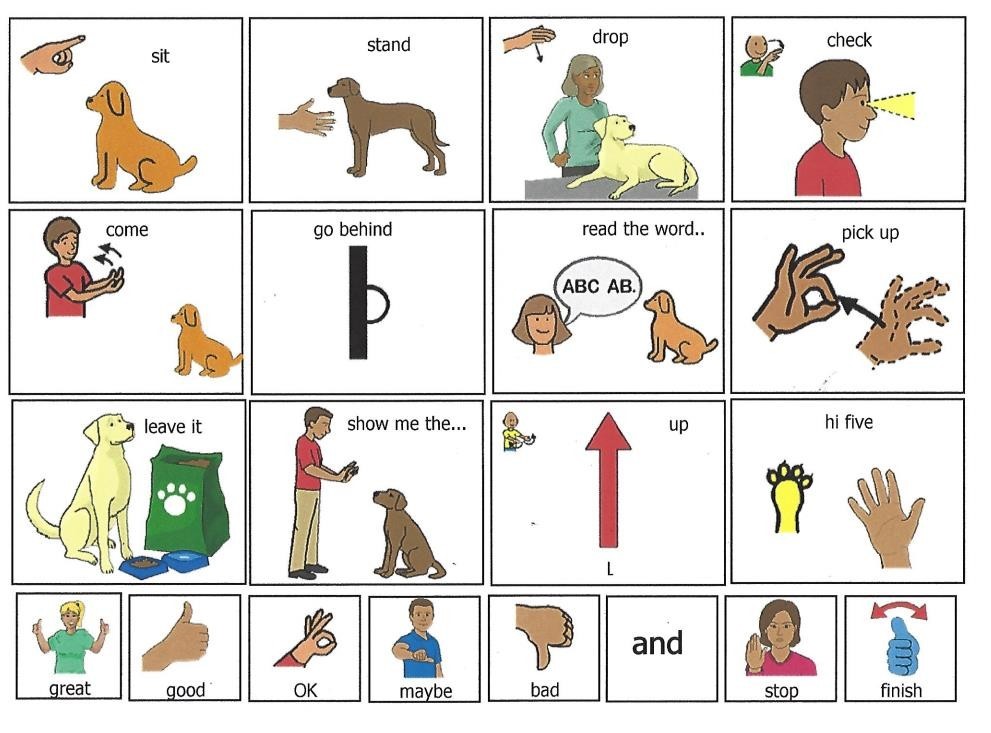

Visual communication chart to help people to see how language can be represented and images pointed to © Dr. Jane Remington-Gurney

By Dr. Jane Remington-Gurney

Introduction

In the literature of journal articles, news stories and websites, animals are often reported to have the ability to improve the well-being of people.

Components of well-being include improved interpersonal and communication skills, sense of purpose and motivation, fine motor skills, strength and balance, self-esteem, and self-worth plus a reduction in anxiety and depression, feelings of loneliness and isolation.

My role as a speech language pathologist (SLP) is to assist people to communicate as, only too often, communication, and ultimately conversation, is elusive and challenging for many people with disabilities.

Being unable to communicate or being incommunicado, is arguably the worse form of human torture. Therefore, if a partnership of handler with a trained and consenting therapy dog can facilitate even a small reduction of the frustration, anxiety and sadness that having a communication impairment brings with it, then the process needs to be explored.

This article will discuss some of the features of my work in the context of therapy dog interventions.

What Is a Therapy Dog?

A therapy dog is a trained dog that may happily provide support to an intervention across a variety of settings with supervision from a trained and accredited handler.

A therapy dog is not an assistance or service dog. Ideally, the dog must be registered with an official organization and, like its handler, have specific training and accreditation.

The refereed and non-refereed literature is rich in descriptions of what a therapy dog is and how they perform their role.

Levinson (1962) describes the therapy dog as a co-therapist. Others note that they have the potential to be an “accelerator,” a “catalyst,” and a “buffer” in therapeutic interventions.

Cariad Pet Therapy (2022) notes that, in a therapy dog intervention there is a “[a] partnership between a consenting therapy dog and its compassionate owner to improve the wellness of themselves and others through human-animal engagements.”

Human-Animal Engagements

These human-animal engagements can take place in many different environments and contexts and have been reported over several hundred years.

More recently, a study by Machová and her colleagues (2018), examined the use of the therapy dog in interactions with people with development dysphasia1 and reported “statistically significant improvement in some primary outcome measures for the experimental group over the control group,” where conventional speech therapy was used.

In 2019, Anderson et al. reported that their study “results suggest that animal-assisted therapy is a potentially valuable tool for speech-language pathologists working with children who have severe delays in communication skills.”

In the same year, Hill (also an occupational therapist) was the lead author of an article that reported on a systematic review of the literature surrounding autistic spectrum disorder (ASD) social behaviors and the role of canine-assisted interventions.

The article by Hill et al. called for more robust measures to be used by researchers but acknowledged that “dogs demonstrate abstract thinking, as well as understanding for both verbal and non-verbal language, for example, following gesture and eye-gaze.” (Hill et al., 2019, p.613).

Meanwhile, Gee et al. (2021) draw our attention to the impact of the therapy dog within the biopsychosocial model to human “self,” noting positive impacts in the domains of biological, psychological, and social well-being.

Finally, Delta Therapy Dogs (2022) encapsulates the use of the therapy dog as a “goal-directed intervention in which an animal that meets specific criteria is an integral part of the treatment process.”

Animal Welfare and the Five Freedoms

Reference to therapy dog interactions and outcomes within the context of domains is also a feature referred to by Mellor et al. (2020) and their work towards a revision of the Five Freedoms in animal welfare.

Therapy dog interventions fall into Animal Assisted Therapy and governance through policies, practice and ethical guidelines and scant legislation.

Animal Assisted Interventions International (2021) notes that the overarching goal is to “promote well-being and benefits for humans and provide a positive experience for the animal without force, coercion, or exploitation.” (p.3).

Within the governance, there are standards for accreditation, and for practice, and standards for the ethical participation of all participants.

There is also strong reference to the Five Freedoms in animal welfare (Brambell, 1965), which are:

- Freedom from hunger and thirst.

- Freedom from discomfort.

- Freedom from pain, injury, or disease.

- Freedom to express normal behavior.

- Freedom from fear and distress.

However, in recent years there has been a proposal to move away from these five freedoms to a model of five domains as “an explicit means to effectively and systematically” evaluate animal welfare and consider the implications to a wide range of human–animal interactions (Mellor et al., 2020).

As my own research applied the theory of dynamic systems, I was drawn to this model and the reference to “dynamic interactivity of virtually all mechanisms in the body” and the potential for “imbalances or disruptions” (Mellor et al., 2020).

The interconnectivity of systems or domains with attention drawn to all participants in an interaction is something that can be explored at a macro or, using transcription notation, at a micro level.

What Is a Speech Language Pathologist?

An SLP, also known as a speech therapist, provides assessments and interventions that aim to improve or maintain any aspect of communication, conversation, and oral skill activities such as eating and drinking.

The assistance provided by a SLP may be directed towards people who have acquired their disability as a result of an injury or illness, or it may be developmental.

As a speech language pathologist working in the field of severe communication impairment, I work with people who have limited or no functional speech and also, people who have difficulties with social understanding and appropriate expression of social language.

With the onset of COVID, my service delivery switched predominantly to online and included the creation of online and self-paced training courses for communication partners.

Visual Communication

The majority of my clients use Key Word Signing and visual communication displays or assistive technologies. They rely on visual language, strategies that maintain good sensory regulation and excellent communication partner skills.

Whilst most of my clients have ASD, some also have challenges that include epilepsy, poor emotional regulation, central auditory processing disorder, attention deficit and delayed integration of reflexes.

These issues can precipitate the need to respond with accommodations such as maintaining a calm, but conducive learning environment and an environment that is fun, motivating and enjoyable for everyone (including the therapy dog).

Implications for the Client and the Therapist

The majority of reports that I have read in the literature indicate that a therapy dog can act as an accelerator to therapeutic interventions and that positive changes are often seen in contexts where there is less “risk of criticism, rejection, evaluation, punishment, inattention, judgment and unsolicited advice.” (LaFrance, Garcia & LaBreche, 2006, p.1).

LaFrance, Garcia & LaBreche (2006) also note that the therapy dog may be a “catalyst for breaking this negative cycle of social interaction in persons with aphasia.”

The therapy dog offers no judgment to how communication might be expressed. Macauley (2006) refers to this as the “unconditional acceptance for the disordered speech that is produced” and adds that the adults with aphasia in her study, “enjoyed the AAT sessions more than the traditional sessions and looked forward to their therapy sessions when the dog would be present with great anticipation.” (Macauley, 2006, p.363).

Whether in a triangular or diamond formation2, there are important implications for the speech language pathologist who is seeking to engage with clients on a regular basis with strategies and tools that have been shown to produce positive outcomes in a fun and engaging environment.

Transcription

There are also implications for researchers and clinicians, as shown in Olga Solomons’ work (2010), for the use of transcription to better understand what is happening in interactions where a therapy dog is used and why.

My own research examined human-centered relationships and part of this exploration was to use transcription and notations for a micro analysis of what happened in interactions and how.

In the process, I identified literature that used transcription and notation for interactions where animals, such as dogs (Tannen, 2004) was involved.

Describing Child-Therapy Dog Interactions

Although time consuming, transcription is a useful tool to ‘see’ what happens and provide a depth that goes beyond merely describing interactions. For example, compare the following:

a) A description of an event that includes a therapy dog handler, the dog, and a teenager

The Therapy Dog is sitting between the handler and the teenager. The teenager calls the dog “,” and the dog goes to him.

b) A transcribed and notated version where the interaction records eye gaze, proximity, timing, volume, wait time and body language

Handler 1 > Therapy Dog 2> <Teenager (smiling)

Teenager: (…3) Loo=cee

Dog: (eye gaze back to handler) Handler: ᵒyesᵒ

Dog: (…2) {tail wagging symmetrically} moves to teenager {opens arms}

Interpretation

The Therapy dog is positioned within 1 meter (1.094 yards) of the handler and 2 meters of the teenager.

While the handler’s gaze is to the dog, the teenager, and the dog share eye gaze.

After 3 seconds the teenager calls the dog’s name with a loud and sing song tone.

Immediately the dog looks to the handler who replies ‘Yes’ in a very soft tone.

After a 2 second delay, the dog moves to the teenager.

In this transcription it can be seen that the dog is responding to the handler.

Arguably, the second way of recording an interaction with transcribed observations provides a clearer view of the sequence of events and the turn taking that occurred.

A Therapy Dog in My Clinic

After completing my Ph.D in Strategies and Styles used by communication partners, I was keen to learn more about the sixth conversation style that my research had identified.

This style was labelled “you, me and something else” and featured interactions where there was an object or something else as an integral part of a conversation. This was inspired by the work of Tannen and later by Christina Hunger.

My golden retriever Charlotte had graduated at Level 4 obedience and was able to ‘watch my back,’ recall off leash, listen solely for her name followed by a cue, and move through distraction mazes.

Together, we completed our Therapy Dog Handler course and began working as a team. When Charlotte passed away unexpectedly, her successor, Bonnie began her Therapy Dog journey with me.

I use a therapy dog in my clinic to assist my clients and the people who provide client support to learn about five key components of conversation: vocabulary, attention/eye contact, turn taking, and self-regulation. I will now discuss these in more detail.

-

Vocabulary

One of the tools used in my work is the communication dictionary.

This is used to record a person’s vocabulary – noting not just the word. but how it is expressed, what it means and what the communication partner should do in response.

Here is an example:

| Word or signal | How it is said | What it means | How you can respond |

| I stiffen my | With extreme | Please stop talking or go away, this is my time! | Acknowledge and be quiet or politely leave. |

| body and | tension like a | ||

| grizzle. | spasm | ||

| Turn my head to | Very small and subtle | Yes | Acknowledge and develop the conversation. |

| left | |||

| ‘4 o’clock?’ | Without question | Please reassure me that mum is coming home at 4 o’clock. | Acknowledge calmly, |

| tone (as yet) | reassure and try to divert

gently. Use Key Word Signing and visual language tools. |

© Dr. Jane Remington-Gurney

As you can see, whether the word is spoken or non-spoken, there is a significant need to know and understand what each signal means.

The same hold true for a dog’s vocabulary. So, in sessions we might explore what the therapy dog signals are, what they might mean and why.

| Word or signal | How it is said | What it means | How you can respond |

| Offers left paw | Little skip | Help me…..I | Think about context. She may want you to find

something or give her something (including information) |

| movement of paw | want… | ||

| from sitting

position. |

May also be used

when she has lost something or is confused. |

||

| Yawn | Looks just like a

‘tired’ yawn but dog not tired. |

I am stressed or I am picking up on your stress. | Check self and context for stress dog may be experiencing. Remove or modify stressor. |

| Eye gaze to toilet | Very quick eye gaze. Sometimes

with a shuffle back to get your eye contact again and she repeats herself. |

I want an empty toilet roll. | Tell her ‘finished’ or ‘all gone’ and do NOT give her

empty toilet rolls. |

| roll holder, and | |||

| then in sequence | |||

| to floor where | |||

| toilet rolls are and | |||

| up to shelf where | |||

| new ones kept. |

© Dr. Jane Remington-Gurney

This can be a valuable activity, particularly if carers are of the belief system that speech is the only vehicle for thought or that non-speech methods are too hard for anyone to learn.

It can be quite revealing to see just how much a person with communication disability can communicate. After all, not being able to speak doesn’t mean a person has nothing to say.

I also make a visual communication chart for some people to see how language can be represented and images pointed to. For example, I might ask a client what they see the dog doing or how they would give feedback (see featured image, top of page).

-

Turn Taking

Turn taking happens when one person allows time for another person to share their thoughts with spoken or non-spoken language.

Often, my clients will need to learn about interruption and providing sufficient wait time for a smooth and fluent exchange of turns to take place.

In my experience, using choice making activities with the therapy dog can be a great way to demonstrate the turn taking process and that conversation can be framed within a sequence of someone initiating (often with a question), another person responding (the answer) and the first person then providing feedback.

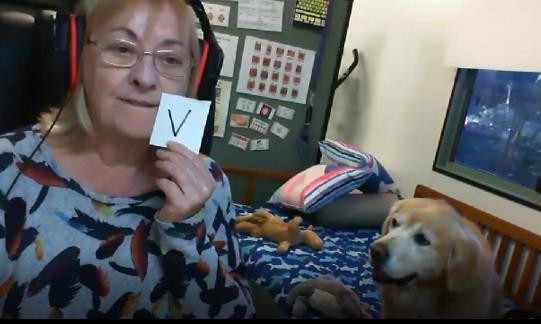

Charlotte takes it in turns with the online client to see what is involved in the activity ‘touch’ for the toy that I name (rat/cat; phone/bone). For example, wait for the person to stop speaking, have a stable base of support, look, listen, think about the answer, then answer © Dr. Jane Remington-Gurney

Bonnie is doing a similar task to Charlotte but with household objects. These ‘tricks’ are consensual and the dog enjoys them for short periods of time © Dr. Jane Remington-Gurney

These activities might also open opportunities for discussion of emotional responses, clarification, and repair strategies in conversation.

For example, how do you feel when you get an answer wrong? How can you say that again in a polite way? What happens when someone doesn’t wait until the speaker has finished before they answer?

-

Attention and Eye Contact

Some of my clients may have compounding or co-morbid challenges, including attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

They may find showing attention through active looking and listening, a huge challenge. They may also not have the social understanding to know that a communication partner relies on certain non-verbal signals to make judgements.

As one client once said, “Wow! So you mean I got all those detentions just for not looking at the teacher when she was talking to me? But I WAS listening!”

Eye contact can be particularly challenging but in our culture it remains, “a fundamental aspect of nonverbal communication.” (Jongerius et al., 2020).

Davidhizar (2016) notes that “lack of eye contact may be interpreted as lack of interest or concern, lack of agreement or preoccupation with something else.”

One thing I have noticed is that eye contact, attention to person, and duration of attention to all stages of conversation appear more sustained and enjoyed when there is a therapy dog involved.

Eye contact at greeting and farewell © Dr. Jane Remington-Gurney

Eye contact to screen © Dr. Jane Remington-Gurney

Eye contact to learn © Dr. Jane Remington-Gurney

Often I will screen shot from recorded sessions for additional teaching purposes and to provide visual information in the form of a Social Story.

| Watching the Shape of the Mouth | ||

|

|

Social Story written for client participating in this session:

Jane helps me with new speech sounds.

Some speech sounds have shapes that I can make with my mouth.

I will try to watch Jane’s mouth and the shapes it makes.

This is a helpful thing to do. |

|

© Dr. Jane Remington-Gurney

Charlotte shows active looking © Dr. Jane Remington-Gurney

When clients get visual materials featuring the therapy dog, it comes as no surprise that it’s the dog that receives the Christmas cards and thank you notes for “helping me talk!”

-

Self-Regulation

Being in a state of emotional regulation that is conducive to learning is paramount.

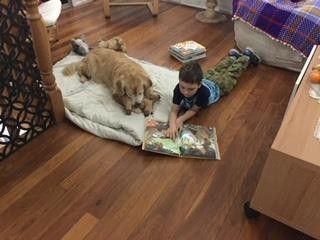

The literature notes the potential value of the presence of a dog to elicit calm and a higher quality of expressive language and social interaction in informal and formal environments (see The use of dogs in the courtroom and Story Dogs).

However, not everyone is comfortable in the presence of a dog and at no time should inclusion of a therapy dog in session be anything but consensual.

Similarly, I have found it to be essential that I have a clear understanding of what the triggers are for my clients; triggers that can take them from calm to a meltdown in the blink of an eye. At no time should there be any risk of harm to any party in any session. This is why we have risk assessments.

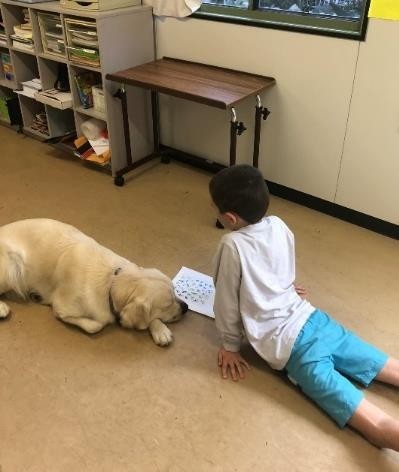

The non-judgmental contribution made by the therapy dog in interactions can add to the depth of meaning, pleasure, and pride that a client experiences by having a therapy dog in the same environment, whether it be for reading, exercise, or conventional speech therapy activities.

Duration to task may also be extended for some clients – perhaps because the dog contributes to the four Cs in my work ethic: calm, cheerfulness, companionship, and care.

The non-judgmental contribution made by the therapy dog in interactions can add to the depth of meaning, pleasure, and pride that a client experiences © Dr. Jane Remington-Gurney

Summary

The literature shows that therapy dogs have a valuable role in the clinical and therapeutic situation, but more research is needed to help guide the training of handlers, the collection of data, and the design of intervention programs.

It would be interesting to see whether the use of transcription and notation can shed more light on the roles played by therapy dog and the handler. They are after all, a team.

Therapy dogs have a valuable role in the clinical and therapeutic situation © Dr. Jane Remington-Gurney

The author would like to extend her special thanks to Heidi Hamilton, Hilary Paull and Sam King for their information sharing and down-to-earth approach.

1Aphasia/dysphasia is the language disorder that results from damage to the areas of the brain responsible for language. This includes written, spoken, and non-spoken language.

2Triangular formation includes the clinical handler, client, and therapy dog whereas the diamond formation includes a clinician who is not the dog handler.

References

Anderson, H.K., Hayes, S.L., & Smith, J.P. (2019). Animal Assisted Therapy in Pediatric Speech- Language Therapy with a Preschool Child with Severe Language Delay: A Single-Subject Design. The Internet Journal of Allied Health Sciences & Practice 17(3) 1

Animal Assisted Interventions International. (2021). Animal Assisted Activity (AAA): Standards,

General Competencies, Accreditation Processes and Manual, and Glossary

Brambell, R. (1965). Report of the technical committee to enquire into the welfare of animals kept under intensive livestock husbandry systems. London, UK: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office

Cariad Pet Therapy. (2022). Our Ethos

Davidhizar, R. (2016). Interpersonal Communication: A Review of Eye Contact. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press

Delta Therapy Dogs. (2022). Delta Therapy Dogs Program

Gee, N.R., Rodriguez, K.E., Fine, A.H., & Trammell, J.P. (2021). Dogs Supporting Human Health and Well-Being: A Biopsychosocial Approach. Frontiers in Veterinary Science 30 8:630465

Hill, J., Ziviani, J., Driscoll,C., & Cawdell-Smith, C. (2019). Can canine-assisted interventions affect the social behaviors of children on the autistic spectrum? A systematic review. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 6:13–25

Jongerius, C., Hessels, R., Romijn, J., Smets, E., & Hillen, M. (2020). The Measurement of Eye Contact in Human Interactions: A Scoping Review. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior 44

LaFrance, C., Garcia, L.J., & Labreche, J. (2006) The effect of a therapy dog on the communication skills of an adult with aphasia. Journal of Communication Disorders 40(3):215-24

Levinson, B. (1962). The dog as a “co-therapist”. Mental Hygiene 46 59–65

Macauley, B. (2006). Animal-assisted therapy for persons with aphasia: A pilot study. Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development. 43(3) P.357-366.

Machová, K., Kejdanová, P., Bajtlerová, I., Procházková, R., Svobodová, I., & Mezian, K. (2018). Canine-assisted Speech Therapy for Children with Communication Impairments: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Anthrozoös 31 5

Mellor, D.J., Beausoleil, N. J, Littlewood, K.E., McLean, A.N., McGreevy, P.D., Jones, B., & Wilkins, C.(2020). The 2020 Five Domains Model: Including Human-Animal Interactions in Assessments of Animal Welfare. Animals 10 (10):1870

Resources

Hunger, C. (2021). How Stella learned to talk : the groundbreaking story of the world’s first talking dog. Crows Nest, N.S.W., Australia: Allen & Unwin

Lunkenheimer, E. (2018). Dynamic Systems Theory. The SAGE Encyclopedia of Lifespan Human Development. SAGE.

Reide, D. (1987) The relationship between man and horse with reference to medicine throughout the ages. People, Animal, Environment 5(2)

Remington-Gurney, J.S. (2017). Conversations Without Speech: A qualitative investigation of the strategies used by adult communication assistants in Queensland

Solomon, O. (2010). What a Dog Can Do: Children with Autism and Therapy Dogs in Social Interaction. Ethos 38: 143-166

Spruin, E., Holt, N., Franz, A., & Fernandez, A. (2016). The use of dogs in the courtroom

Tannen, D. (2004). Talking the dog: Framing pets as interactional resources in family discourse. Research on Language and Social Interaction 37(4), 399-420