My dog Huckleberry and my kitten Cato play rough-and-tumble games all day. Huckleberry chases Cato, Cato pounces on her neck, Huckleberry fake-bites his leg, he jumps on her belly and fake-gnaws her ear. They’re friends. Not “friends” like the dog and cat who sleep together in the dog’s bed because it’s the softest, warmest spot in the house and they both want to stake their claim to it. Real friends, who have devised a code of fair play that transcends their differences in size, strength and species. You can watch their antics here; it gets really good around 1:30: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gH-78g1-1Qw&spfreload=10

Don’t get me wrong–Huckleberry will still snark at Cato if he gets near her stuff. And naturally, the more valuable the resource, the more ferociously she guards it from him. As with so many interactions between potential rivals in the animal world, these displays of aggression are just that–displays. I’ve witnessed many. There’s no escalation, and Cato, though unafraid, takes the hint and backs off. He doesn’t take umbrage, Huckleberry doesn’t hold a grudge. They forgive and forget–or probably just forget, period–in the next instant.

Don’t get me wrong–Huckleberry will still snark at Cato if he gets near her stuff. And naturally, the more valuable the resource, the more ferociously she guards it from him. As with so many interactions between potential rivals in the animal world, these displays of aggression are just that–displays. I’ve witnessed many. There’s no escalation, and Cato, though unafraid, takes the hint and backs off. He doesn’t take umbrage, Huckleberry doesn’t hold a grudge. They forgive and forget–or probably just forget, period–in the next instant.

The other day Huckleberry was finishing up some delectable morsel of someone’s breakfast leftovers, awarded to her for staying in her bed instead of begging at the table at meal time. Cato just happened to be in the neighborhood and thought he’d pop by. Huckleberry gave a snarl that escalated into a roar, and charged at him in a particularly disagreeable manner. As usual, no harm, no foul. Cato didn’t even leave the scene, he simply parked himself on the family room rug a few feet away from Huckleberry’s bed while she finished her yummy tidbit. Just another day in the life….

But wait…there’s more. Seconds after lashing out at Cato, Huckleberry got up from her bed, walked over to him, and lay down next to him, on her side with her belly exposed, which is her standard invitation for him to jump on top of her. When he didn’t respond to this overture, she reached out a paw and tenderly patted his head. He licked her paw. And moments later, they were romping again.

But wait…there’s more. Seconds after lashing out at Cato, Huckleberry got up from her bed, walked over to him, and lay down next to him, on her side with her belly exposed, which is her standard invitation for him to jump on top of her. When he didn’t respond to this overture, she reached out a paw and tenderly patted his head. He licked her paw. And moments later, they were romping again.

OK, where am I going with this? What’s the punchline? Is there a moral? Does there need to be? I want to believe my dog apologized to my cat. Nope, I can’t prove it. I know about all the research that tells us dogs don’t feel guilt or regret, and when they seem guilty or regretful, they’re merely responding appeasingly to our own heated emotions. And yes, I know it’s entirely possible that by the time this poignant (to me) exchange happened, Huckleberry and Cato had already literally forgotten the whole flare-up and were just ready to play again.

On the other hand, Huckleberry never initiates play by lying on her side. She usually starts things off by chasing and stomping and pinning and coming on too strong till Cato grumbles at her to dial it back a bit. In fact, lying on her side is a self-handicapping maneuver. She humbles herself. She typically assumes this posture to induce Cato to keep playing when he’s grown weary of her overbearing ways. So I stand by the story I’ve been telling myself. Huckleberry felt sorry about snapping at her friend, and she was trying to say, “No hard feelings?”

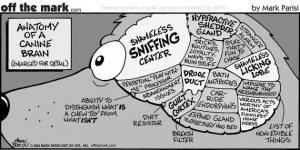

We’ve come a loooooong way in the debate about whether animals even have emotions. Breakthroughs in neuroscience in recent decades have yielded new clarity about the structures and functions of the human brain. Animal brains can be studied and better understood using the same tools and methods. Comparisons can be made. Science now can validate what we’ve intuited all along: Animals have emotions. But our capacity to fathom those feelings, to plumb their depths, remains limited indeed.

We’ve come a loooooong way in the debate about whether animals even have emotions. Breakthroughs in neuroscience in recent decades have yielded new clarity about the structures and functions of the human brain. Animal brains can be studied and better understood using the same tools and methods. Comparisons can be made. Science now can validate what we’ve intuited all along: Animals have emotions. But our capacity to fathom those feelings, to plumb their depths, remains limited indeed.

Last fall I took Susan Friedman’s scintillating online course on applied behavior analysis called “Living and Learning with Animals”. I found her exploration of animal learning absolutely riveting. But Dr. Friedman never missed an opportunity to caution us that animal behaviorists can only analyze behavior that is “overt”, i.e. that which they can can observe. “Covert” behavior–what an animal is thinking or feeling–can’t be described objectively, and they are therefore off-limits in the scientific study of animal behavior. The internal mental states of our dogs and cats (and the rest of the creatures on our planet) are still invisible to us and out of our reach.

Earlier in this piece I “operationalized” my dog’s actions toward my cat–that is, documented what I saw. I could then parse out the antecedents and consequences in the standard applied behavior analysis template, and this would go a long way to helping me hypothesize and test what triggered the behaviors in question, and whether the behaviors will increase or decrease in the future. It’s a fascinating exercise and an effective tool for behavior modification. But if I want to grasp why Cato and Huckleberry (and all the other animals in my world) do the things they do, what motivates their choices, what drives their decisions? This still remains dishearteningly opaque. When we venture into this territory, we’re just guessing, or–sin of sins!–anthropomorphizing. How many of us are wishing for a real-life version of the translation collar worn by Dug the dog in the Disney Pixar film “UP”!? https://video.disney.com/watch/meeting-dug-4be70ed17401eb6a6e9faf04

Earlier in this piece I “operationalized” my dog’s actions toward my cat–that is, documented what I saw. I could then parse out the antecedents and consequences in the standard applied behavior analysis template, and this would go a long way to helping me hypothesize and test what triggered the behaviors in question, and whether the behaviors will increase or decrease in the future. It’s a fascinating exercise and an effective tool for behavior modification. But if I want to grasp why Cato and Huckleberry (and all the other animals in my world) do the things they do, what motivates their choices, what drives their decisions? This still remains dishearteningly opaque. When we venture into this territory, we’re just guessing, or–sin of sins!–anthropomorphizing. How many of us are wishing for a real-life version of the translation collar worn by Dug the dog in the Disney Pixar film “UP”!? https://video.disney.com/watch/meeting-dug-4be70ed17401eb6a6e9faf04

So my anecdote about Huckleberry’s apology to Cato is just that–anecdotal. It’s the crudest possible study, with a sample size of one. Conclusion: Inconclusive. Yet as pet owners and animal lovers, we live for this stuff. We’re constitutionally incapable of simply being objective observers. We can’t help but interpret, speculate, ascribe intent. All behavior becomes dialogue in our running narrative about our lives with animals. We imagine what they’re saying to us or each other. We see good will, or forgiveness, even a sense of humor in their actions. Or we ascribe darker purpose to their behavior: they’re resentful, jealous, mad at us. I even found a scenario very similar to the one I described above in the “Ask the Experts” section of Dognition’s web site. The author of the query witnessed a scuffle between her two dogs, and what appeared to be a gesture of reconciliation that immediately followed, and said “I’d be interested in knowing if this was a type of doggie ‘apology'” (see https://support.dognition.com/forums/193007-ask-an-expert/suggestions/6640142-do-dogs-apologize-to-one-another). I hope someone at Dognition will address the question soon!

Maybe I should just speak for myself. I long to read my dog’s mind. Part of why I became a dog trainer was to have a window into the souls of these familiar yet enigmatic beings. And now I do, once in a while, feel like Dr. Dolittle–for example when I see subtle signs of anxiety like a tongue flick or a mouth clamping shut and I know a dog is worried even if his owner doesn’t. I know my bond with my dog is built on love and trust that goes both ways, and I don’t need to prove it to anyone or have anyone prove it to me. But I do wonder if there will ever come a day when we can know what animals are thinking and feeling–when those covert internal states will be visible to us in some form, through some mode. Is this impossible for today, or impossible forever? Or maybe some things are just better left undone. I’m starting to get into science fiction–not to mention bioethics–territory, i.e. out of my depth. So I’ll end here, with a question:

Maybe I should just speak for myself. I long to read my dog’s mind. Part of why I became a dog trainer was to have a window into the souls of these familiar yet enigmatic beings. And now I do, once in a while, feel like Dr. Dolittle–for example when I see subtle signs of anxiety like a tongue flick or a mouth clamping shut and I know a dog is worried even if his owner doesn’t. I know my bond with my dog is built on love and trust that goes both ways, and I don’t need to prove it to anyone or have anyone prove it to me. But I do wonder if there will ever come a day when we can know what animals are thinking and feeling–when those covert internal states will be visible to us in some form, through some mode. Is this impossible for today, or impossible forever? Or maybe some things are just better left undone. I’m starting to get into science fiction–not to mention bioethics–territory, i.e. out of my depth. So I’ll end here, with a question:

What do you think would happen if we could be like Dr. Dolittle, or if our dogs could be like Dug from “Up!” with a talking collar that translates their thoughts? How would it change us, them, our lives, their lives, the world?!